Nicaragua’s Caribbean Coast, where the sea is a source of life and livelihood, is overshadowed by a tragic reality: shipwrecks.

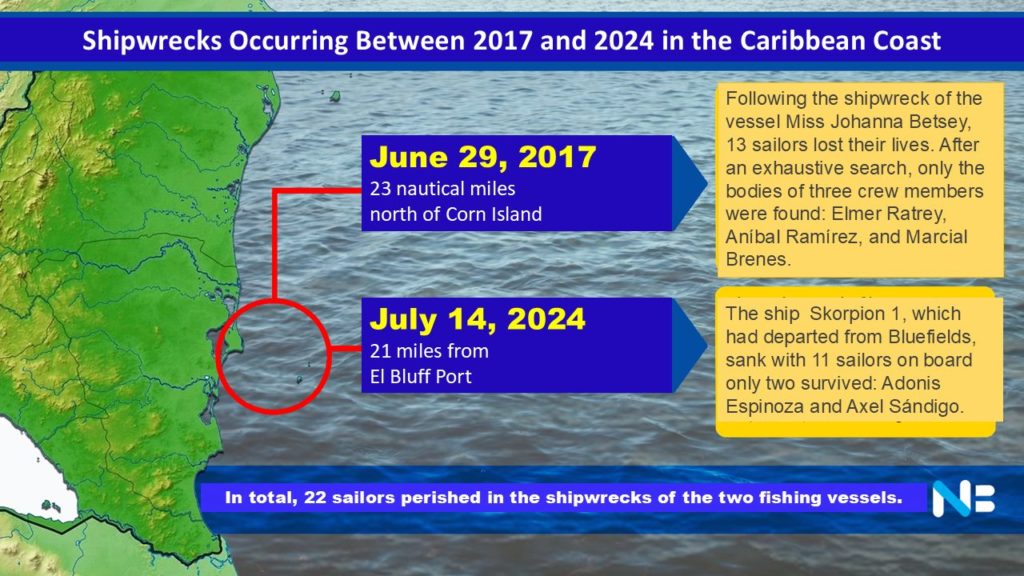

These tragedies, far from being isolated incidents, reveal precarious working conditions and an alarming lack of safety for those who make their living from fishing. Two shipwrecks, the “Johana Betsey” seven years ago and the “Scorpion 1” in 2024, have left a deep wound in the community of Bluefields, in Nicaragua’s Southern Caribbean region, plunging more than 22 families into grief and uncertainty.

In this special report from Noticias de Bluefields, learn more about the dimensions of a tragedy that has marked the life of an entire region.

The pain of absence: Job’s case

During Christmas 2024, the family of Job Eliú Guillén García, a 25-year-old fisherman, experienced an inevitable void. Job was one of nine people who died in the sinking of the “Scorpion 1,” which set sail from Bluefields on July 14 with 11 fishermen aboard. Only two survived.

Despite adverse weather conditions with storms in the forecast, the vessel received authorization to depart. Job’s body was found in Costa Rican waters and repatriated to Bluefields, allowing his family to say a final goodbye—an opportunity that families of the other fishermen did not have.

From the age of 13, Job dedicated himself to fishing to support his family. Before finding his passion at sea, he worked as a taxi driver and also in journalism. Influenced by his brothers and attracted by the economic opportunities fishing offered, Job became a beloved member of the community, recognized for his restless spirit, charisma, and generosity. He often shared lobsters, shrimp, and fish not only with his family but also with neighbors. His mother, Alba Seferina García, remembers him fondly:

“He always brought fish to share.” However, like other fishermen, Job faced high risks each time he set sail due to the vessels’ lack of safety measures and the unpredictable weather.

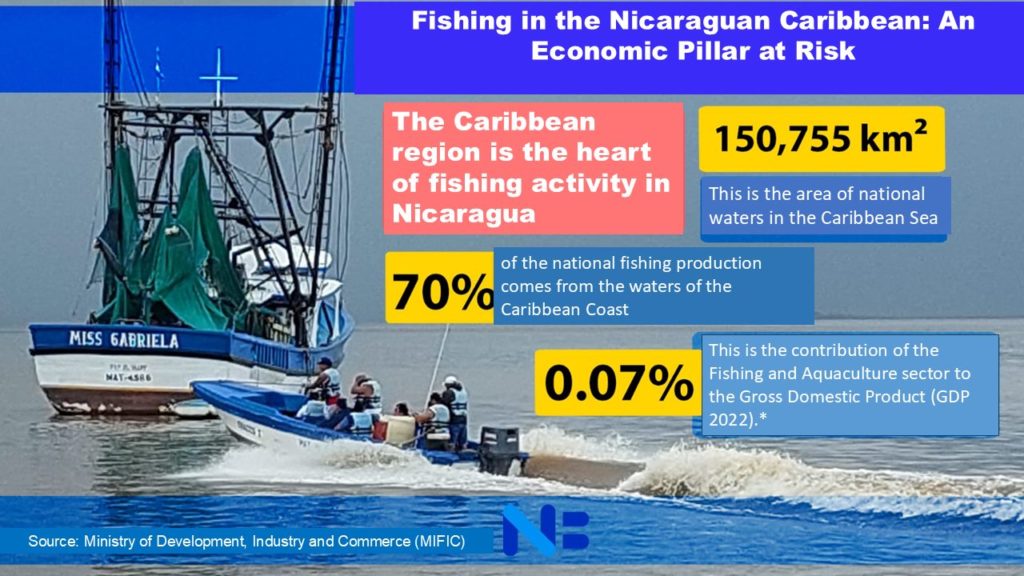

A vital but precarious and unsafe industry

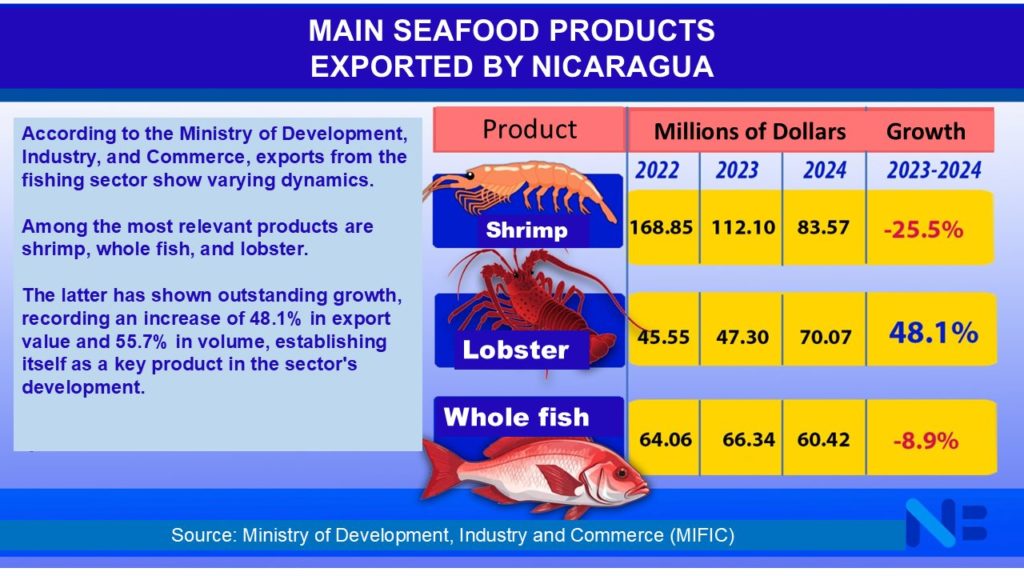

Fishing is crucial to the Caribbean Coast’s economy, generating millions of dollars in exports. However, this wealth doesn’t translate into better conditions for artisanal fishermen who risk their lives due to a lack of employment alternatives. As Alba Seferina laments, “They go to sea with the hope of returning, but they don’t know if they’ll come back alive.”

Fishing represents an important source of income for Nicaragua, with exports exceeding $250 million in 2022, according to data from the Export Processing Center (CETREX), and reaching $23 million in the first half of 2024 to China alone, according to Edward Jackson, executive president of the Nicaraguan Institute of Fisheries and Aquaculture (Inpesca). However, this bonanza does not translate into improvements in occupational safety for artisanal fishermen.

Francisco Guillén, Job’s father, indignantly denounces that “fishermen work as if they were disposable.” The vessels lack basic safety equipment such as life jackets, emergency rafts, and monitoring systems. Additionally, they have no life insurance or support in case of accidents.

The region faces maritime tragedies that reveal serious deficiencies in safety protocols. For David Rizo Zelada, Job’s cousin, prevention is crucial. “If the vessels were in better condition and the authorities acted more quickly, many lives would be saved,” he states. Rizo emphasizes that, even days after the shipwreck, there was still hope for rescue.

The Case of the Johana Betsey

The sinking of the “Scorpion 1” is not an isolated case. On June 29, 2017, the fishing boat “Miss Johana Betsey” sank with 13 sailors on board. Only the boat and the bodies of three fishermen were found. Ten families were left without the possibility of saying goodbye to their loved ones.

Aracely Lazo González, 17, who graduated from high school late last year, still feels the absence of her father, Rolando Lazo Villareal, one of those who disappeared in this shipwreck. Rolando, who had been fishing since before his daughter’s birth, was trying to support his family. Aracely recounts with anguish that the boat on which her father died was not designed for so many people or for open sea conditions.

The need to support his family drove him to embark. “My mom told me that he became more responsible since they were together. He worked to provide, but we never imagined this would happen,” says Aracely, overcome by nostalgia and resignation.

Testimonies of pain and loss

Fermina Aragón Mendoza, mother of Genaro González, one of the crew members who died in the Scorpion 1 shipwreck in July last year, remembers with deep pain the day she learned of the tragedy: “When they told me the boat had disappeared, my world fell apart. I worked in a bakery, but the pain prevented me from continuing.”

Genaro, described by his mother as a humble and calm young man, had gone to sea hoping to gather money for his family’s subsistence. “He shared the little he brought from the sea; he always gave fish to me and friends,” Fermina recounts. Despite the time that has passed, the pain persists: “Every mother who has lost a child feels the same. The Lord is the only one who can give us the strength to move forward.”

Fermina calls on authorities and young fishermen to prioritize safety: “I would recommend not going to sea when there is bad weather. Better to work on land, because it’s the mothers who suffer, and we never see them again.”

Zuny Rivera Navarro, mother of Alder Alvarado, another fisherman who disappeared on the Scorpion 1, remembers that this was her son’s last trip. He would have turned 30 in July, the month of the tragedy. Despite the bad weather, Alder explained to her that they would go out to set traps. His mother remembers him as a hardworking and dedicated young man. She directly points to the owner of the Scorpion 1, Leslie Downs, and the naval authorities for negligence: “All those deaths are on a single conscience.”

She also highlights the crucial role of the Bluefields community in the search, in contrast to the inaction of institutions. Alder’s family still struggles to accept his absence: “Each day that passes, the hope that he will return fades a little more, like a candle,” his mother shares.

Zuny, along with other affected families, demands greater controls and supervision in fishing activities: “Boat owners should be more concerned about the lives of their crew members than about their economic interests.”

Mother sailed to Costa Rica in search of her son

After receiving the devastating news, Sorayda Jiménez undertook a tireless search for her son Kenny Hernández, leaving Bluefields aboard a speedboat and reaching Barra de Colorado in Costa Rica, defying adverse weather conditions.

Her son was an experienced fisherman with six years of experience at sea. Sorayda remembers that Kenny had expressed concern about the boat’s condition before setting sail. “It’s a very great pain; his absence is felt at home. I have no words to express it because it’s as if we’ve been torn apart inside,” said Sorayda.

The family of sailor Juan Carlos Zambrana Matute, 30, who also died after the Scorpion 1 shipwreck, was able to say a final goodbye. His body was found on July 21, 2024, on the beaches of Tortuguero, Costa Rica, and after months of waiting, the family managed to repatriate his remains on January 19, 2025. The body was identified through a genetic test performed on his mother, Norma Matute.

Vulnerable family economy

Fishing is the main source of income for many families on Nicaragua’s Caribbean coast. However, they depend on weather conditions and fishing seasons. An experienced fisherman can earn up to 50,000 córdobas (USD 1,365.21) during a 45-day work period, but this money must cover basic needs for several months. This includes paying for food, clothing, footwear, medicine, and water and electricity services.

The families of deceased fishermen have received insufficient economic compensation and pensions that barely cover a fraction of their needs. The lack of financial support and limited follow-up by authorities worsen their situation. Although there is no official figure, one source indicates that the 13 affected families received little more than 100,000 córdobas (about USD 2,730) each, in two payments: first 40,000 córdobas (USD 1,090) and the rest over the course of a year.

The family of Ronaldo, one of the deceased fishermen, received a small compensation from the boat owner, Eduardo Zeledón. His daughter, Aracely, receives a monthly pension from the Nicaraguan Social Security Institute (INSS) of just over 1,000 córdobas (USD 27.30), an insufficient amount to cover her basic expenses. “What we receive is very little compared to the cost of things today,” she laments. Her mother works in a local business to support the household.

Job’s tragic death left his family in a critical economic situation, as he was the main provider. His elderly parents are grateful for the community’s solidarity but express disappointment over the authorities’ lack of response in investigating the case. They live in a humble wooden house in the San Mateo neighborhood of Bluefields municipality, owned by a daughter who struggles to cover her parents’ basic needs: food, utilities, and medicines.

According to the Nicaraguan Institute of Information for Development (Inide), the basic food basket in Nicaragua exceeds 21,000 córdobas (USD 580), reflecting the extreme vulnerability of fishing families, whose income barely allows them to cover expenses for two months. This precariousness worsens during the lobster fishing ban (April-June) when, due to lack of alternatives, some fishermen resort to informal jobs or trap manufacturing in exchange for state aid of 500 córdobas (USD 13) per month.

Despite state propaganda about economic prosperity, the eighth survey on the Perception of Nicaragua’s Political, Social, and Economic Reality conducted by Hagamos Democracia in September 2024 reveals that 99.5% of Nicaraguans have a negative perception about the country’s future. Nine out of ten claim their income is insufficient to cover basic needs. This perception contrasts with figures from the Central Bank of Nicaragua (BCN), which projects economic growth of 3.5% to 4.5% for 2025.

However, for Caribbean fishing families, the lack of job opportunities forces them to continue this activity despite the enormous risk it poses to their lives.

Women adrift economically

In Bluefields, a region where six ethnic groups share life, the families of fishermen who died in shipwrecks face very serious economic and social challenges. In this context, women have become heads of their households, struggling to support their families through informal work such as street vending, cleaning, and commerce.

Nineteen women now have to take charge of the economy and emotional well-being of their homes. This is very difficult in a region with few opportunities for them and where Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo’s regime does not offer many basic services. There are no public or private programs supporting these women and their children.

“We live in our daughter’s house who is working in the United States, and now we depend on her help for our illnesses,” says Alba Seferina García, mother of Job Guillén, one of the victims of the Scorpion shipwreck.

In this community, where families are large and help each other, grandparents play an important role in childcare. But the lack of basic services makes the situation even more difficult. According to data from Nicaragua’s Ministry of Education (MINED), Bluefields has 28 primary schools, but there are no daycare centers for childcare. Additionally, there is only one regional hospital, and for serious cases or those requiring specialized care, families must travel eight hours to Managua or wait months to be treated by social security, if they have it.

The fishermen’s families are doubly vulnerable: first, due to the lack of security that caused the death of their loved ones, and second, due to the lack of support from the regime. Although authorities said they helped during the search and transport of bodies, the women were left without long-term protection, having to bear the burden of supporting their families in a place with no opportunities for their well-being.

Despite all these difficulties, these women are very strong and struggle to survive and support their families. However, it is urgent that public policies be created that include these women and guarantee their access to basic services, community development, and equality for the women of Bluefields.

The Interactive Map of the Zero Usury Program , which promises accessible credit for women’s development, indicates that in Bluefields municipality, 6,540 loans have been delivered, amounting to 55,917,700 córdobas (USD 1,526,792.32). However, this program has not reached the families of these fishermen.

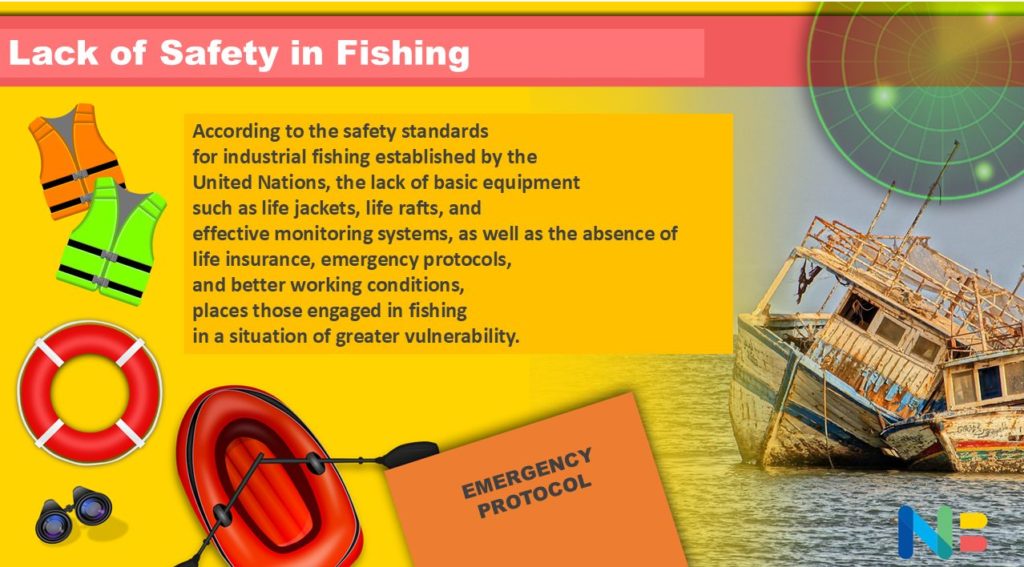

Deficiencies in safety and legal framework

The tragedy of the Scorpion 1 shipwreck reveals serious deficiencies in maritime safety protocols: the delayed response from authorities and the lack of basic equipment, such as life rafts and effective monitoring systems, may have contributed to the magnitude of the tragedy. The lack of strict protocols and the use of inadequate vessels are urgent issues. This situation contrasts with the reality of fishermen who, faced with lack of opportunities, face a sea of risks, where work seems to be a death sentence. The fishing boat Scorpion 1 sank in Caribbean waters on Sunday, July 7; of the crew, only two fishermen managed to survive: Adonis Espinoza and Axel Sándigo, who were rescued on July 16 in Costa Rican waters. The shipwreck, according to survivors, was due to improper distribution of cargo, which included more than 200 traps and sand.

The lack of social security for Caribbean fishermen in Nicaragua remains an outstanding debt, despite clear legal provisions that require fishing companies to guarantee this protection.

The Fisheries and Aquaculture Law 489, in its Article 52, establishes that “Holders of licenses, concessions, and permits must comply with the legal and labor provisions established for fishing activity, including those concerning social security.” The same article emphasizes the responsibility of license holders and vessel captains. However, these regulations are not enforced, leaving affected families unprotected.

Between 2015 and 2024, more than 30 shipwrecks have been reported on the Caribbean Coast, with dozens of lives lost. In 2022 alone, six serious incidents were recorded, according to the Naval Force of the Nicaraguan Army. In most of these cases, adverse weather conditions and lack of safety protocols were determining factors. It is urgent that authorities, vessel owners, and communities work together to implement measures that guarantee safety at sea, from providing life insurance to training in emergency protocols.

The impact of climate change and FAO/IMO recommendations

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), in the last decade, fishermen’s safety in the region has been severely affected by the impacts of climate change, with more frequent and severe storms and hurricanes, as demonstrated by Hurricanes Eta and Iota in 2020.

The International Convention on Standards of Training, Certification and Watchkeeping for Fishing Vessel Personnel (STCW-F) of the IMO establishes minimum training standards for crews, seeking to safeguard lives and protect the marine environment.

The FAO recommends the use of life jackets, helmets, appropriate footwear, gloves, and thermal clothing, in addition to rescue devices such as rafts, flares, distress signals, first aid kits, fire extinguishers, and thermal blankets, especially for small-scale fishing vessels, which often operate in precarious conditions.

The shipwrecks have left a deep trauma in families that has not yet been adequately addressed by psychosocial support professionals. The absence of bodies complicates the acceptance of loss, generating an “ambiguous grief,” according to psychologist Luis Barrera. This type of grief makes it difficult to close the cycle in a traditional way, preventing the wake and burial.

Barrera explains that families typically experience phases such as denial and anger before acceptance and suggests performing symbolic acts, such as religious ceremonies, to honor the memory of the disappeared and find comfort in the community. The sea is life, and sometimes death, in the Caribbean of Nicaragua.

LEER TAMBIÉN Saving shipwrecked people: a community commitment in Tasbapouine